Review: Nauticam 140mm dome port by Alex Mustard

Field Review: Nauticam 140mm dome on Full Frame

By Alex Mustard.

Introduction

The bigger your sensor the bigger your dome port needs to be to give good corner sharpness with wide angle lenses underwater. I’ll get into the detail of that sweeping statement further down the page, but before I send you to sleep, the key message is mini domes are troublesome on full frame cameras. The main problem is that the corners of the frame go completely blurred. And these troubles are even worse with rectilinear lenses than with fisheyes. Ultimately if you want the best dome port performance out of your full frame camera you have to invest in a large, expensive dome port. But over the last 5 years (when their popularity was reignited with introduction of the Zen 100), many photographers have experienced first hand the advantages of mini-domes. So the big question is how small can you go on full frame?

If small domes are not as good optically as big domes, why use one? First they are cheaper to buy, smaller and lighter for travel. They don’t add as much buoyancy to your housing, avoiding the wrist aching upward torque that large domes produce. Photographically they allow us to get the lens even closer to the subject and their small dimensions make it easier to light a subject when it is very close to the lens.

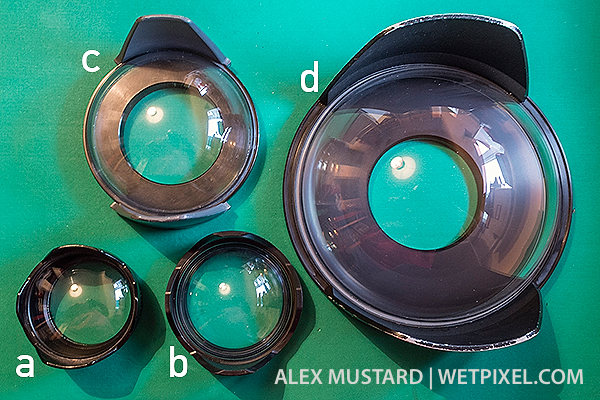

I have long concluded that 140-150mm (approx. 5.5-6”) is the sensible lower limit with a fisheye on full frame. Indeed in 2010 I commissioned my own one-off dome at exactly this size, which has been an active part of my arsenal ever since (this year, for example, shots taken with my 150mm acrylic dome and Nikon D4, won me two categories in the British Wildlife Photography Awards – the certificates arrived in the post today!). For this reason I was excited to try Nauticam’s new 140 glass dome in the Red Sea with the new Nikon D750 (which I’ve reviewed separately).

Why Size Matters

It is always a challenge to discuss dome optics without everyone loosing the will to live. My intention here is to cover the important practical principles in plain language, knowingly risking the wrath of pedants with some intentional oversimplification.

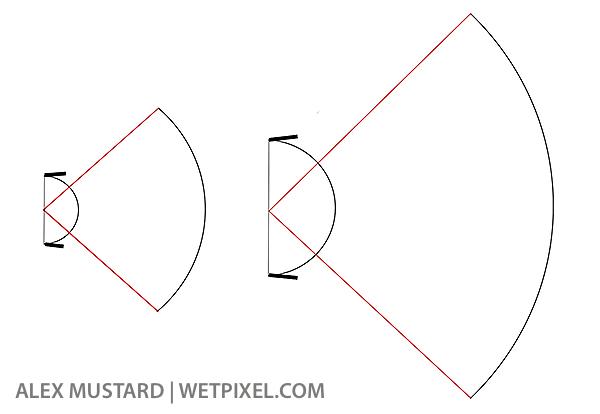

We use dome ports underwater because they maintain the angle of view of our wide angle lenses (1). But in water, dome ports act as a lens and create a virtual image of the subject much closer to the camera than the true subject (2). The camera has to focus on this virtual image, but it is curved (in parallel with the dome) and lenses focus on flat planes. If we shoot with the lens wide open (usually f/2.8) then the centre of the image will be in focus, but the rest will be out of focus, increasingly blurred towards the corners. This is because of the curvature of the virtual image we’re trying to focus on. The solution is to close the aperture to increase depth of field and bring the corners back into focus.

The closer we focus a lens, the less depth of field we get (3) (something you’ll know well if you shoot supermacro). A mini dome creates a virtual image that is closer and more tightly curved than a big dome. Therefore the lens has to focus close, lowering depth of field, and it has more of a challenge anyway, to keep the corners of the virtual image within the depth of field because of they are more curved. The result: smaller domes produce images with softer corners3.

The shorter the focal length of lens (the wider it is) the more depth of field it has (3). You already know your wide angle has more depth of field that your macro lens. As a result, camera formats (crop factors) become important. Smaller formats use shorter focal length lenses (with more depth of field) for the same angle of coverage. For example a 180 degree fisheye lens on a 2x crop Olympus OM-D camera has a focal length of 8mm, a 180 degree fisheye on a 1.5x crop Nikon D7100 is a 10mm and a 180 degree fisheye on a 1x crop (full frame) Nikon D4 is a 15mm. All have a field of view of 180 degrees corner to corner, but the 8mm (being a shorter focal length) has more depth of field at any aperture and subject distance. In practice this means we can use smaller domes with the smaller formats and maintain the same corner sharpness.

I use all three of these systems in my photography and have mini-domes for each. I use an 80mm dome with the 8mm on the 2x crop, a 100mm port with the 10mm on the 1.5x crop and a 150mm port with the 15mm on the 1x crop. This for me is the lower limit of acceptable quality and all require me to close the aperture of my lenses to achieve corner sharpness. Larger domes on each system make it much easier to get sharp corners (4).

The final factor to mention is that fisheye lenses are more suited to working behind domes than rectilinear (none fisheye lenses). The result is that rectilinear lenses require larger domes than fisheyes to achieve comparable corner sharpness.

Notes On This Section:

(1) They also correct the pincushion distortion and chromatic aberrations inherent in using a flat port, which get increasingly stronger the wider we try and view through a flat port.

(2) This is why when we shoot split level images we must focus on the underwater section of the scene and use depth of field to ensure the above water view is in focus (above water there is no virtual image). Depth of field extends twice as far behind a subject than in front of it, so we should always focus on the closest subject to have both sharp. If photographers mistakenly focus on the above water element in a split level image, the underwater section will invariably be out of focus. Furthermore, since big domes have a virtual image further from the dome they are more suited to these shots as this makes it easier to have both the underwater virtual image and the above water (no virtual image) within the depth of field. They also make controlling the water surface easier.

(3) These comments are simplifications, assuming everything else is equal!

(4) The earliest domes were all small. In the early 1960s both Schulke and Starck pioneered the use of hemi-spherical domes, independently. Realising the limitation of their small domes sourced from boat compasses, they dreamed of larger domes if only they could be made. They can now. Smaller domes have advantages, but they also have compromises, and when using them we should always remember that the pioneers of dome ports dreamed of escaping them!

Page 1. Overview of dome ports.

Page 2. Review of Nauticam 140mm dome port.